Author Archive

The Wouff Hong

The Wouff Hong

One of the most interesting and unique artifacts from the early days of radio was not powered by batteries nor did it have any electronic components. I far as I can tell, Radio Shack never stocked it on their shelves and you can’t order it from Ham Radio Outlet.

From the 1969 ARRL “Radio Amateur’s Operating Manual”:

Every amateur should know and tremble at the history and origins of this fearsome instrument for punishment of amateurs who cultivate bad operating habits and who nourish and culture their meaner instincts on the air…

This is the Wouff Hong.

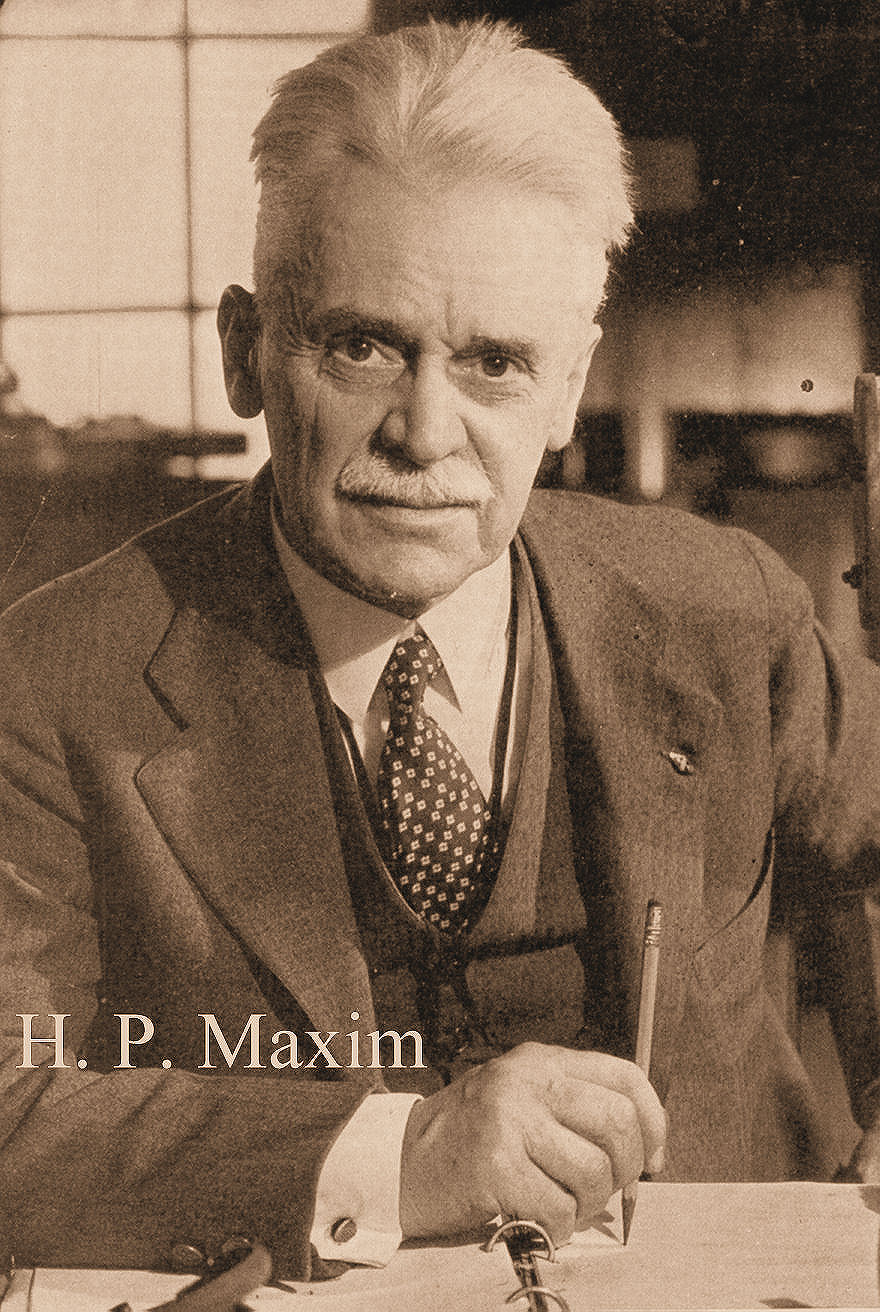

It was invented -or at any rate, discovered- by “The Old Man” himself, just as amateurs were getting back on the air after World War One. “The Old Man” (who later turned out to be Hiram Percy Maxim, W1AW, Co-founder and first president of ARRL) first heard the Wouff Hong described amid the howls and garble of QRM as he tuned across a band filled with signals which exemplified all the rotten operating practices then available to amateurs, considering the state of the art as they knew it. As amateur technology and ingenuity have advanced, we have discovered new and improved techniques of rotten operating, but we’re ahead of our story.

As The Old Man heard it, the Wouff Hong was being used on some hapless offender so effectively that he investigated. After further effort, “T.O.M.” was able to locate and identify a Wouff Hong. He wrote a number of QST articles about contemporary rotten operating practices and the use of the Wouff Hong to discipline the offenders.

Early in 1919, The Old Man wrote in QST “I am sending you a specimen of a real live Wouff Hong which came to light out here . . . Keep it in the editorial sanctum where you can lay hands on it quickly in an emergency.” The “specimen of a real live Wouff Hong” was presented to a meeting of the ARRL Board and QST reported later that “each face noticeably blanched when the awful Wouff Hong was . . . laid upon the table.” The Board voted that the Wouff Hong be framed and hung in the office of the Secretary of the League and there it remains to this day, a sobering influence on every visitor to League Headquarters who has ever swooshed a carrier across a crowded band.

The Old Man never prescribed the exact manner in which the Wouff Hong was to be used, but amateurs need only a little i

imagination to surmise how painful punishments were inflicted on those who stoop to liddish behavior on the air.

Read more about the Wouff Hong:

http://amfone.net/WouffHong/wouff.htm

http://www.netcore.us/wh/

http://everything2.com/title/Wouff+Hong

… and you can buy your very own miniature replica of the Wouff Hong in the form of a pin from ARRL. Now how cool is that?

Classic Radio Periodical Covers

Classic Radio Periodical Covers

Like others, I enjoy learning about the early history of radio. It gives me an idea of how far the hobby and technology has come as well as inspiring the imagination.

I found a great site, MagazineArt.org, which allows the viewer to peruse many of the covers from a variety of periodicals from the early days of the wireless.

Check out some of them here:

Popular Radio

Radio Age

Radio Craft

Radio News

The Wireless Age

Shortwave Craft

NPR: Celebrating 100 Years of Ham Radio

NPR: Celebrating 100 Years of Ham Radio

To be able to go out to a park somewhere and literally throw a length of wire into a tree and sit down and talk with somebody in, say, Italy, is endlessly thrilling to me. – Sean Kutzko, KX9X

A recent NPR story with a visit to W1AW. Check it out here.

I’m a little envious of Sean Kutzko’s visit to W1AW.

I think this is a great characterization of the hobby that always inspires the imagination (well, at least mine)

…he’s contacted others all across the globe – coral atolls in the South Pacific, even a research station in Antarctica.

Makes me want to spark up the rig and see what I can find.

PEARL HARBOR: PATTON VS THE SIGNAL CORPS

PEARL HARBOR: PATTON VS THE SIGNAL CORPS

“Getting the Message Through: A Branch History of the U.S. Army Signal Corps” by Rebecca Robbins Raines

CENTER OF MILITARY HISTORY, UNITED STATES ARMY, WASHINGTON, D.C., 1996 (pgs 242-244)

During 1940 President Roosevelt had transferred the Pacific Fleet from bases on the West Coast of the United States to Pearl Harbor on the Hawaiian island of Oahu, hoping that its presence might act as a deterrent upon Japanese ambitions. Yet the move also made the fleet more vulnerable. Despite Oahu’s strategic importance, the air warning system on the island had not become fully operational by December 1941. The Signal Corps had provided SCR-270 and 271 radar sets earlier in the year, but the construction of fixed sites had been delayed, and radar protection was limited to six mobile stations operating on a part-time basis to test the equipment and train the crews. Though aware of the dangers of war, the Army and Navy commanders on Oahu, Lt. Gen. Walter C. Short and Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, did not anticipate that Pearl Harbor would be the target; a Japanese strike against American bases in the Philippines appeared more probable. In Hawaii, sabotage and subversive acts by Japanese inhabitants seemed to pose more immediate threats, and precautions were taken. The Japanese-American population of Hawaii proved, however, to be overwhelmingly loyal to the United States.

Because the Signal Corps’ plans to modernize its strategic communications during the previous decade had been stymied, the Army had only a limited ability to communicate with the garrison in Hawaii. In 1930 the Corps had moved WAR’s transmitter to Fort Myer, Virginia, and had constructed a building to house its new, high-frequency equipment. Four years later it added a new diamond antenna, which enabled faster transmission. But in 1939, when the Corps wished to further expand its facilities at Fort Myer to include a rhombic antenna for point-to-point communication with Seattle, it ran into difficulty. The post commander, Col. George S. Patton, Jr., objected to the Signal Corps’ plans. The new antenna would encroach upon the turf he used as a polo field and the radio towers would obstruct the view. Patton held his ground and prevented the Signal Corps from installing the new equipment. At the same time, the Navy was about to abandon its Arlington radio station located adjacent to Fort Myer and offered it to the Army. Patton, wishing instead to use the Navy’s buildings to house his enlisted personnel, opposed the station’s transfer. As a result of the controversy, the Navy withdrew its offer and the Signal Corps lost the opportunity to improve its facilities.

Though a seemingly minor bureaucratic battle, the situation had serious consequences two years later. Early in the afternoon of 6 December 1941, the Signal Intelligence Service began receiving a long dispatch in fourteen parts from Tokyo addressed to the Japanese embassy in Washington. The Japanese deliberately delayed sending the final portion of the message until the next day, in which they announced that the Japanese government would sever diplomatic relations with the United States effective at one o’clock that afternoon. At that hour, it would be early morning in Pearl Harbor.

Upon receiving the decoded message on the morning of 7 December, Chief of Staff Marshall recognized its importance. Although he could have called Short directly, Marshall did not do so because the scrambler telephone was not considered secure. Instead, he decided to send a written message through the War Department Message Center. Unfortunately, the center’s radio encountered heavy static and could not get through to Honolulu. Expanded facilities at Fort Myer could perhaps have eliminated this problem. The signal officer on duty, Lt. Col. Edward F French, therefore sent the message via commercial telegraph to San Francisco, where it was relayed by radio to the RCA office in Honolulu. That office had installed a teletype connection with Fort Shafter, but the teletypewriter was not yet functional. An RCA messenger was carrying the news to Fort Shafter by motorcycle when Japanese bombs began falling; a huge traffic jam developed because of the attack, and General Short did not receive the message until that afternoon.

PEARL HARBOR: PATTON VS THE SIGNAL CORPS

PEARL HARBOR: PATTON VS THE SIGNAL CORPS

“Getting the Message Through: A Branch History of the U.S. Army Signal Corps” by Rebecca Robbins Raines

CENTER OF MILITARY HISTORY, UNITED STATES ARMY, WASHINGTON, D.C., 1996 (pgs 242-244)

During 1940 President Roosevelt had transferred the Pacific Fleet from bases on the West Coast of the United States to Pearl Harbor on the Hawaiian island of Oahu, hoping that its presence might act as a deterrent upon Japanese ambitions. Yet the move also made the fleet more vulnerable. Despite Oahu’s strategic importance, the air warning system on the island had not become fully operational by December 1941. The Signal Corps had provided SCR-270 and 271 radar sets earlier in the year, but the construction of fixed sites had been delayed, and radar protection was limited to six mobile stations operating on a part-time basis to test the equipment and train the crews. Though aware of the dangers of war, the Army and Navy commanders on Oahu, Lt. Gen. Walter C. Short and Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, did not anticipate that Pearl Harbor would be the target; a Japanese strike against American bases in the Philippines appeared more probable. In Hawaii, sabotage and subversive acts by Japanese inhabitants seemed to pose more immediate threats, and precautions were taken. The Japanese-American population of Hawaii proved, however, to be overwhelmingly loyal to the United States.

Because the Signal Corps’ plans to modernize its strategic communications during the previous decade had been stymied, the Army had only a limited ability to communicate with the garrison in Hawaii. In 1930 the Corps had moved WAR’s transmitter to Fort Myer, Virginia, and had constructed a building to house its new, high-frequency equipment. Four years later it added a new diamond antenna, which enabled faster transmission. But in 1939, when the Corps wished to further expand its facilities at Fort Myer to include a rhombic antenna for point-to-point communication with Seattle, it ran into difficulty. The post commander, Col. George S. Patton, Jr., objected to the Signal Corps’ plans. The new antenna would encroach upon the turf he used as a polo field and the radio towers would obstruct the view. Patton held his ground and prevented the Signal Corps from installing the new equipment. At the same time, the Navy was about to abandon its Arlington radio station located adjacent to Fort Myer and offered it to the Army. Patton, wishing instead to use the Navy’s buildings to house his enlisted personnel, opposed the station’s transfer. As a result of the controversy, the Navy withdrew its offer and the Signal Corps lost the opportunity to improve its facilities.

Though a seemingly minor bureaucratic battle, the situation had serious consequences two years later. Early in the afternoon of 6 December 1941, the Signal Intelligence Service began receiving a long dispatch in fourteen parts from Tokyo addressed to the Japanese embassy in Washington. The Japanese deliberately delayed sending the final portion of the message until the next day, in which they announced that the Japanese government would sever diplomatic relations with the United States effective at one o’clock that afternoon. At that hour, it would be early morning in Pearl Harbor.

Upon receiving the decoded message on the morning of 7 December, Chief of Staff Marshall recognized its importance. Although he could have called Short directly, Marshall did not do so because the scrambler telephone was not considered secure. Instead, he decided to send a written message through the War Department Message Center. Unfortunately, the center’s radio encountered heavy static and could not get through to Honolulu. Expanded facilities at Fort Myer could perhaps have eliminated this problem. The signal officer on duty, Lt. Col. Edward F French, therefore sent the message via commercial telegraph to San Francisco, where it was relayed by radio to the RCA office in Honolulu. That office had installed a teletype connection with Fort Shafter, but the teletypewriter was not yet functional. An RCA messenger was carrying the news to Fort Shafter by motorcycle when Japanese bombs began falling; a huge traffic jam developed because of the attack, and General Short did not receive the message until that afternoon.

The Final Courtsey

The Final Courtsey

The static crashes were coming more frequently now and I could see the lightning off in the distance. I had been driving since the early afternoon and only had about two hours left until I arrived home. The sun had set an hour ago but the moon was not up yet and it was dark as pitch. My headlights cut through the night. Shortly before the Autumn sunset, the clouds moved in from the west with the winds gusting against my pickup truck as I headed south. The rain was off and on, more of a nuisance than an impediment to driving.

It had been a long day of meetings and I looked forward to getting behind the wheel. My mobile setup in the pickup is simple: an IC-706MKIIG and a screwdriver antenna – just 100 watts. It was relaxing to hear the rush of white noise as the rig powered up and my screwdriver antenna spun up to a good match for 40 meters. I had enjoyed a few QSOs as I barreled down US Interstate 29. Traffic was light. After the sun set, the band started to go long and decided to drop down 75 meters. The screwdriver antenna coil whirled again, sending the whip up a bit higher.

As I slowly spun the dial, I heard a call coming just above the S5 noise level. “CQ CQ CQ, this is W0XRR, Whiskey Zero X-ray Romeo Romeo, calling CQ and listening.”

Gripping the handmike, I replied to the call, “W0XRR, this is Kilo Delta Seven Papa Juliet Quebec, KD7PJQ, the name is Scott and I am mobile, south on I-29.” Releasing the Push To Talk button, the noise rushed back to fill the cab of my pickup. The rain started to pick up, beating against the roof and windshield as I continued south.

“NI0L, Scott, fine business and thank you for answering my call. Name here is Bert, Bravo Echo Romeo Tango. My QTH is just outside of Atchison, Kansas – Atchison, Kansas. Good signal tonight, I would not have guessed you were mobile. Ok Scott, back to you.” Bert’s signal had gotten stronger and I easily copied him through the noise. His audio quality was as smooth as silk… no processing.

“Solid copy all Bert, you’ve got a solid signal tonight, started off a bit weak but has picked up to a solid 57 to 58. Ok on your QTH in Atchison. I am headed south on I-29. Just passed Hamburg and crossed into Missouri from Iowa. My destination is not far from your QTH. I am headed to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Back to you, Bert.” Despite the poor weather on the road, I was anticipating this was going to be a good QSO and hoped our ragchew would keeping me company on a pretty miserable evening to be out on the road.

“Well Scott, I am glad to make the contact. The weather is bad here and I imagine it is worse up your way. I was down here in my basement shack and decided I would warm up the tubes and see what I could find on the bands. Ok on Fort Leavenworth, just a bit south from here. I have not been out to the fort for a number of years but know it well. I retired sometime back and now spend a lot more time down here in the basement either spinning the dial or tinkering with one project or another. Lets hear from you, Scott. What’s put you out on the road tonight?” Bert asked.

I told Bert how I had been at a conference on Offutt Air Force Base in Nebraska. The event had ended a day early and I was trying to make my way back home to see the family and enjoy a full weekend. I explained how I had been in the Army for over two decades, had originally gotten my call when I was stationed at Fort Lewis, Washington, and had recently been transferred to Fort Leavenworth with my family. “We really enjoy the area. I am thinking about retiring there in Leavenworth. Back to you, Bert,” my index finger released the PTT.

Bert came back to me with his signal competing with the noise floor. “Fine business all, Scott. I used to be in the Signal Corps and did 30 years in the Army. Was stationed out there at the fort for my last assignment as well. Good posting there at Leavenworth. Glad to hear you and your family are enjoying it.” He told me about how he used to support an air defense unit that was stationed on Fort Leavenworth. His signal detachment was responsible for integrating all the communications for the Nike missile batteries in Kansas, Missouri, and Nebraska. We continued to trade war stories for another twenty minutes or so. Then his signal began to fade.

“I am starting to loose you Bert, so I better wrap this up. I really appreciate the QSO and to make the contact. Any chance you will be at the hamfest in Raytown coming up the Saturday after next? A few miles southeast of Kansas City? It would be a great opportunity for an eyeball QSO… and I am buying the coffee. What do you say? Back to you, Bert.” The rain was a constant downpour now, rolling across the road in front of me.

No reply was heard except for a few static crashes from the lightning. “W0XRR, this is KD7PJQ, thanks again for the contact, 73 Bert!”

I had begun making my deliberate ‘s’ pattern through the rows of gear (… and, lets be honest, junk) when I saw a table with some nice Collins gear. There was the transmitter (a 32S-3A), a receiver (75S-3C), and even a Collins 30L-1 amplifier. The bearded oldtimer manning the table had his undivided attention focused on a breakfast burrito and it took a moment for him to wash down a deliberate bite with a drink of coffee.

“Good morning. Nice Collins S-Line! These are in great shape – looks like they’ve been well cared for. You don’t see these everyday. Why are you selling them?” I heard older hams talk about these Collins rigs, but I had never seen them before.

“Good morning… sorry you caught me in the middle of breakfast. Yup, this is a nice set. Not mine actually. We’re selling it for the widow of a Silent Key. I’ve got more boxes here of his stuff. I think all the manuals are in one of these,” the gentleman said as he turned in his seat a leaned over to pull an open box towards him.

“The lady gave us a call to come and clear out the ham shack. He’d passed away last year but it took her until now to finally part with the gear. We picked everything up earlier in the week. Took us two trips. Here’s one of the manuals,” he said as he handed me the manual for the 75S-3C, yellowed with age but well cared for.

I flipped through the book, noticing the margin notes,,, and then a QSL card fell out between the pages and onto the table. I looked at the callsign on the card – …W0XRR. Bert McKenzie, Atchison, Kansas. There was a picture of a Nike-Hercules black and white missile elevated at 45 degrees on a launch platform as well as the crossed semaphore flags of the Signal Corps.

“Wait… who’s gear was this? What was the call of the Silent Key?”

“Well, there’s his QSL card!” The oldtimer pointed to the card on the table. “This gear belonged to Bert… W0XRR,” the oldtimer picked up the QSL card from the table.

“But when was it you said he passed away?” I was confused and trying to sort out what I was hearing.

The oldtimer stroked his beard as he set the QSL card down, with the image of the Nike missile towards the table. “Let’s see… it’s been a little over a year now. Bert passed away last year around the end of October.”

I looked down again at the QSL card on the table. This side of the card had the blanks for QSO specifics. There was handwriting on it and I tentatively lifted the card up to get a better look. On it I saw my call, KD7PJQ…. 75 meters, the date of our QSO (… less than two weeks ago), a 5-7 signal report… and a circle around “PSE QSL”. The card slipped out of my hand and onto the table.

Dazed, I lurched away from the table. I needed fresh air and sunlight.

The oldtimer called after me, “Hey! You interested in the rig? Go ahead and make an offer.”

Author’s note: This story is a work of fiction. Names, characters, call signs, locations, and incidents are products of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.