Posts Tagged ‘Mobile Wireless’

The Future of Emcomm

The Future of Emcomm

Here comes Starlink!

I’ve been reading a number of reports from the areas affected by the two major hurricanes (Helene and Milton). The North Carolina experience is particularly interesting because people have experienced the loss of communication and electrical service for several weeks. I can imagine this same thing happening in other parts of the country, including my area.

I’ve been reading a number of reports from the areas affected by the two major hurricanes (Helene and Milton). The North Carolina experience is particularly interesting because people have experienced the loss of communication and electrical service for several weeks. I can imagine this same thing happening in other parts of the country, including my area.

There are two important technology disruptions showing up in North Carolina: satellite-based internet (Starlink) and mobile-phone-to-satellite (SMS) text messaging. Starlink is having a significant impact during this incident, while mobile phone satellite messaging is still emerging. Steve N8GNJ has some worthy thoughts on these topics in Zero Retires 173. Although I have served in many ARES/RACES deployments over the years, I don’t consider myself an expert in this area. I’d appreciate comments from Emcomm folks who have spent more time thinking about this.

Types of Emergency Communication

Most relevant emergency comms lump into 1) short-range comms (< 5 miles) between family, friends, and neighbors. 2) medium-range comms (50 miles) to obtain information and resources. 3) long-range comms (beyond 50 miles) to connect with distant family, friends, and resources.

- Short-Range Comms: This is the type of communication that is well served by mobile phones, except when the mobile networks are down. This is happening a lot in North Carolina. Lightly licensed VHF/UHF radios such as FRS and GMRS can be used to replace your mobile phone. Think: wanting to call your neighbor 3 miles away to see if they are OK or can provide something you need. (I have a few FRS/GMRS radios in my stash to share with neighbors. See TIDRadio TD-H3) VHF/UHF ham radio is, of course, even better for this, except the parties involved need to be licensed. (OK, you can operate unlicensed in a true emergency, but that has other issues. See The Talisman Radio.)

- Medium-Range Comms: This is a great fit for VHF/UHF ham radio using repeaters or highly-capable base stations. GMRS repeaters can also serve this need. These communications will typically be about situational awareness and resource availability in the surrounding area. For example, someone on the local ham repeater may know whether the highway is open to the place you want to drive.

- Long-Range Comms: Historically, this has been done by HF ham radio and a lot of emergency traffic is still handled this way. The shift that is happening is that setting up a Starlink earth station feeding a local WiFi network can help a lot of people in a very effective manner. Compare passing a formal piece of health-and-welfare traffic via ham radio to letting a non-licensed person simply get Wi-Fi access to their email or text messaging app. Hams are doing this, but many unlicensed techie folks have set up these systems and freely shared them with the public.

Mobile Satellite Messaging

Various providers now offer a basic text messaging capability using smartphones talking to satellites. Today, this capability is often limited to emergencies (“SOS”), and it is relatively slow. With time, this capability will certainly improve and basic satellite texting will be ubiquitous on smartphones. This will be great for checking in with distant friends and families, but it may not be that useful for Short Range and Medium Range comms. Someday, it might include voice comms, but in the near term, it is probably just text-based.

Evan K2EJT provides some useful tips based on his experience here in this video. However, he doesn’t address the Starlink capability.

Summary

While much of the public appreciates the usefulness of ham radio during emergencies, I am already hearing questions like “Doesn’t Starlink cover this need?” My view is that Starlink (and similar commercial sats) is very useful and will play an important emcomm role, but it does not cover all of the communication needs during incidents such as hurricanes, blizzards, wildfires, earthquakes, etc. Emcomm folks (ARES and RACES) will need to adapt their approach to take this into account.

Those are my thoughts. What do you think?

73 Bob K0NR

The post The Future of Emcomm appeared first on The KØNR Radio Site.

Amateur Radio: Narrowband Communications in a Broadband World

Amateur Radio: Narrowband Communications in a Broadband World

For my day job in the test and measurement industry, I get involved in measurement solutions for wireless communications. Right now, the big technology wave that is about to hit is known as 5G (fifth generation wireless). Your mobile smartphone probably does 4G or LTE as well as the older 3G digital mobile standards. For more detail on LTE, see ExtremeTech explains: What is LTE?

For my day job in the test and measurement industry, I get involved in measurement solutions for wireless communications. Right now, the big technology wave that is about to hit is known as 5G (fifth generation wireless). Your mobile smartphone probably does 4G or LTE as well as the older 3G digital mobile standards. For more detail on LTE, see ExtremeTech explains: What is LTE?

5G will be the next cool thing with early rollouts planned for 2018. The design goals of 5G are very aggressive, with maximum download speeds of up to 20Gb/s. (See what I did there: I used the words “up to”, so don’t expect this performance under all conditions.) The actual user experience has yet to play out but we can assume that 5G is going to be blazing fast. For more details see: Everything You Need to Know About 5G. To achieve these high bandwidths, 5G will use spectrum at higher frequencies. Move up in frequency and you inherently get more bandwidth. The FCC recently allocated 11 GHz of new spectrum for 5G, including allocations at 28 GHz, 37 GHz, 39 GHz and 64-71 GHz: FCC 5G spectrum allocation demands 3 breakthrough innovations . Yes, those frequencies are GHz with a G…that’s a lot of cycles per second.

Amateur Radio

So my day job is focused on wider bandwidths and higher frequencies. Then I go home and play amateur radio which is a narrowband, low frequency activity. The heart of ham radio operation is on the HF bands, 3 to 30 MHz, almost DC by 5G standards. Many of us enjoy VHF and UHF but even then most of the activity is centered on 50 MHz, 144 MHz, maybe 432 MHz. I recently started using 1.2 GHz for Summits On The Air, so that at least gets me into the GHz-with-a-G category.

Not only does ham radio stay on the low end of the frequency range, we also use low bandwidth. The typical phone emission on the HF bands is a 3-kHz wide SSB signal. That’s kHz with a k. As we go higher in frequency, some of our signals are “wideband” such as a 16-kHz wide FM signal on the 2m band. In terms of digital modes, AX.25 packet radio and APRS typically use 1200 baud data rates but sometimes we go with a “super-fast” 9600 transmission mode. CW is still a very popular narrowband mode with bandwidths around 200 Hz, depending on Morse code operating speed. Lately, the trend has been to go even narrower in bandwidth to keep the noise out and operate at amazingly low signal-to-noise ratios. Some of the WSJT modes use bandwidths in the range of 4 to 50 Hz.

There are some good reasons that amateur radio remains narrowband. The two most important are:

- We love the ionosphere and what it does for radio propagation. The HF bands are great for making radio signals go around the world but they are narrow spectrum. For example, the 20m band is 350 kHz wide, going from 14.000 to 14.350 MHz. Operation is restricted to narrowband modes, else we’d use up the entire band with just a few signals.

- We just want to make the contact (and maybe talk a bit). For the most part, radio hams are just trying to make the contact. This is most pronounced during a DX pileup or during a contest when you’ll hear short exchanges that provide just the minimal amount of information. Some of us like to talk…rag chew…but that can be accomplished with narrowband (SSB) modulation with no problem. I suppose it would be handy from time to time to be able to send a 3 MB jpg file to someone I am working on 20m but that’s not the main focus of a radio contact.

Of course, not all amateur radio operation is below 1 GHz. There’s always someone messing around at microwave and millimeter wave frequencies. I’ve done some mountaintop operating at 10 GHz and achieved VUCC on that band. Recently, the ARRL announced a new distance record of 215 km on the 47 GHz band.

ICOM produced a D-STAR system at 1.2 GHz with a data rate of 128kbps, quite the improvement over AX.25 packet. However, adoption of this technology has been very limited and it remains a single-vendor solution.

There is significant work going on with High-Speed Multimedia (HSMM) Radio which repurposes commercially-available 802.11 (“WiFi”) access equipment. Broadband-Hamnet is focused primarily on using 2.4 GHz band to create mesh wireless mesh networks. Amateur Radio Emergency Data Network (AREDN) is doing some interesting work, mostly on the 2.4 GHz and 5.8 GHz bands. The HamWAN site has lots of information about a 5.8 GHz network in the Puget Sound area. The basic theme here is use commercial gear on adjacent ham bands…a common strategy for many VHF and higher ham radio systems.

Also worth mentioning is the FaradayRF work, currently aimed at creating a basic digital radio for the 33cm (902 MHz) amateur band. The raw data transfer rate is around 500 kbaud.

There are probably some other high-speed digital systems out there that I’ve missed but these are representative.

Infrastructure Rules

A critical factor in making LTE (and 5G) work is the huge investment in infrastructure by Verizon, AT&T and others. With cellular networks, the range of the radio transmission is limited to a few miles. One of the trends in the industry is toward smaller cells, so that more users can be supported at the highest bandwidths. With 5G moving up in frequency, small cells will become that much more important.

On the other hand, most amateur radio activity is “my radio talking to your radio” without any infrastructure in between. Most of us like the purity and simplicity of my station putting out electromagnetic waves to talk directly to fellow hams. In many cases, this simplicity and robustness has played well under emergency and disaster conditions.

FM (and digital voice) repeaters are a notable exception with the Big Box on the Hill retransmitting our radio signal. For decades now, FM repeaters have represented an infrastructure that individual hams and (more often) radio clubs put in place for use by the local ham community. There is a trend towards more infrastructure dependency in ham radio as repeaters are linked via the internet via IRLP, EchoLink and other systems. (Some hams completely reject any kind of radio activity that relies on established infrastructure, often claiming that it is irrational, unethical or just plain wrong.)

One interesting area that is growing in popularity is the use of hotspots (low power access points) for the digital voice modes (D-STAR, DMR, Fusion, etc.) In this use model, the ham connects a hotspot to their internet connection and talks to anyone on the relevant ham network while walking around the house with a handheld transceiver. See the Brandmeister web site to see the extend of this activity. It strikes me that this is the same “small cell” trend that the mobile wireless providers are following. You want good handheld coverage? Stick a hotspot in your house.

Looking at ham radio and broadband communications, I summarize it like this:

- The vast majority of ham radio activity is narrowband oriented, for reasons described above.

- There is some interesting ham radio work being done with broadband systems, mostly on 2.4 GHz and 5.8 GHz.

- Commercially available broadband technology (LTE, 5G, and beyond) will continue to increase total network bandwidth and performance increasing the difference between commercial broadband and narrowband ham radio.

Implications

The reason for writing this article is that the amateur radio community needs to recognize and understand this increasing bandwidth gap. We like to talk about the cool and exciting stuff we do with wireless communications but we need to also appreciate how this is perceived by someone with an LTE phone in their pocket. Just communicating with someone at a distance is no longer novel. After all, Amateur Radio is Not for Talking.

What do I conclude about this? Here’s a few options:

1. Don’t worry. We are all about narrowband and that’s good enough. This attitude might be sufficient as there are tons of fun stuff to do in this narrowband world. In terms of ham radio’s future, this implies that we need to expose newcomers to narrowband radio fun. We’ll need to get better at talking about how amateur radio makes sense in this broadband world.

2. Embrace commercially available broadband. Use it where it makes sense. This approach means that Part 97 remains mostly narrowband but we can make use of the ever-improving wired and wireless network infrastructure that is available to us.

3. Develop Part 97 ham radio broadband. I am initially a bit skeptical of this idea. How the heck does ham radio compete with the billions of dollars Verizon, AT&T and others poor into broadband wireless? But that may not be the point. Once again, I fall back to the universal purpose of amateur radio: To Have Fun Messing Around with Radios. Can we have fun building out a broadband network? Heck yeah, that sounds like an interesting challenge. Would it be useful? Maybe. Emergency communications might be an appropriate focus and some hams are already working on that. Create a network that operates independent from the commercial internet and make it as resilient as possible.

I think Option #3 is definitely worth considering. What do you think?

73, Bob K0NR

The post Amateur Radio: Narrowband Communications in a Broadband World appeared first on The KØNR Radio Site.

Introducing The Android HT

Introducing The Android HT

Some exciting news wandered into my inbox this past week concerning a handheld radio driven by the Android operating system. The RFinder H1 is an FM plus DMR radio to be released at the end of this month. Click to enlarge the photo to the left to get a better view. I had proposed a similar concept back in 2012: The Android HT, so this radio immediately grabbed my attention.

Details are still a bit thin on the RFinder H1 (pronounced “Ar Finder H 1”) but this video gives you a glimpse of its operation. The 70cm band radio apparently also supports GSM and 4G/LTE mobile phone formats.

There are a few other YouTube videos available, one of which emphasizes the easy programming of the radio using the RFinder online repeater directory. This makes perfect sense and is a great example of the power of a connected device. This feature would be very handy for programming up FM repeaters on the fly and outstanding for dealing with the complexity of DMR settings.

The RFinder H1 includes DMR capability, something I wasn’t thinking of back in 2012. That also makes perfect sense…embracing the growing amateur radio format that is based on industry standards.

Very cool development. What do you think?

73, Bob K0NR

The post Introducing The Android HT appeared first on The KØNR Radio Site.

How About a New 12 Volt Automotive Connector?

How About a New 12 Volt Automotive Connector?

Don’t get me wrong — I do like standard connectors. A while back, I wrote about how the micro-USB connector became the standard power/data connector for mobile phones. Well, that is unless you own an iPhone.

Don’t get me wrong — I do like standard connectors. A while back, I wrote about how the micro-USB connector became the standard power/data connector for mobile phones. Well, that is unless you own an iPhone.

The good news is that we do have a standard power connector for 12 VDC in automobiles. The bad news is that it is an ugly behemoth derived from — can you believe it? — a cigarette lighter. For some background and history, see the Wikipedia article. The Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) has a standard that describes this power connector (SAE J563). Alan K0BG correctly warns us to “never, ever use existing vehicle wiring to power any amateur radio gear” including the 12 volt accessory plug. (I always follow this advice, except in the cases when I don’t.) I also found this piece by Bill W8LV on eham.net that describes the crappiness of these connectors.

Well, there is a new standard power connector showing up in cars: the USB port. These ports provide the data and power interface for mobile phones, integrating them into the auto’s audio system. Standard USB ports (USB 1.x or 2.0) have a 5V output that can deliver up to 0.5A, resulting in 2.5W of power. A USB Charging Port can source up to 1.5A at 5V, for 7.5 W of power. This is not that great for powering even low power (QRP) ham radio equipment.

Now a new standard, USB Power Delivery, is being developed that will source up to 100W of power. The plan is for the interface to negotiate a higher voltage output (up to 20V) with 5A of current. Wow, now that is some serious power. We will have to see if this standard is broadly adopted.

Two things are obvious to me: 1) the old cigarette lighter connector needs to go away and 2) it is not clear what the replacement will be.

What do you think? Any ideas for the next generation of 12V automotive connector?

73, Bob K0NR

The post How About a New 12 Volt Automotive Connector? appeared first on The KØNR Radio Site.

The Completely Updated Incomplete List of Ham Radio iPhone Apps

The Completely Updated Incomplete List of Ham Radio iPhone Apps

It is about time I updated one of my more popular posts about my favorite ham radio apps on the iPhone and IPad. As usual, I will focus on free or low cost (less than $5) apps that I am actively using. Some apps have just disappeared from iTunes and new ones have emerged. While this list is completely updated, it is still incomplete, because there are so many apps to choose from.

It is about time I updated one of my more popular posts about my favorite ham radio apps on the iPhone and IPad. As usual, I will focus on free or low cost (less than $5) apps that I am actively using. Some apps have just disappeared from iTunes and new ones have emerged. While this list is completely updated, it is still incomplete, because there are so many apps to choose from.

From the Simple Utility Category:

Ham I Am (Author: Storke Brothers, Cost: Free) A handy app that covers some basic amateur radio reference material (Phonetic alphabet, Q Signals, Ham Jargon, Morse Code, RST System, etc.) Although I find the name to be silly, I like the app!

Maidenhead Converter (Author: Donald Hays, Cost: Free) Handy app that displays your grid locator, uses maps and does lat/lon to grid locator conversions.

HamClock (Author: Ben Sinclair, Cost: $0.99) A simple app that displays UTC time and local time. This one reads out to the second.

There are quite a few good apps for looking up amateur radio callsigns:

CallBook (Author: Dog Park Software, Cost: $1.99) Simple ham radio callbook lookup with map display.

Call Sign Lookup (Author: Technivations, Cost: $0.99) Another simple ham radio callsign lookup with map display.

There are a few repeater directory apps out there and my favorite is:

RepeaterBook (Author: ZBM2 Software, Cost: Free) This app is tied to the RepeaterBook.com web site, works well and is usually up to date.

For a mobile logbook (and other tools):

HamLog (Author: Pignology, Cost: $0.99) This app is much more than a logbook because it has a bunch of handy tools including UTC Clock, Callsign Lookup, Prefix list, Band Plans, Grid Calculator, Solar Data, SOTA Watch, Q Signals and much more.

To track propagation reports, both HF and VHF:

WaveGuide (Author: Rockwell Schrock, Cost: $2.99) This is an excellent tool for determining HF and VHF propagation conditions at the touch of a finger.

If you are an EchoLink user, then you’ll want this app:

EchoLink (Author: Synergenics, Cost: Free) The EchoLink app for the iPhone.

There are quite a few APRS apps out there. I tend to use this one because my needs are pretty simple….just track me, baby!

Ham Tracker (Author: Kram, Cost: $2.99) APRS app, works well, uses external maps such as Google and aprs.fi. “Share” feature allows you to send an SMS or email with your location information.

Satellite tracking is another useful app for a smartphone:

Space Station Lite (Author: Craig Vosburgh, Cost: Free) A free satellite tracking app for just the International Space Station. It has annoying ads but its free.

ProSat Satellite Tracker (Author: Craig Vosburgh, Cost: $9.99) This app is by the same author as ISS Lite, but is the full-featured “pro” version. Although it is a pricey compared to other apps, I recommend it.

For Summits On The Air (SOTA) activity, there are a few apps:

Pocket SOTA (Author: Pignology, Cost: $0.99) A good app for finding SOTA summits, checking spots and accessing other information.

SOTA Goat (Author: Rockwell Schrock, Cost: $4.99) This is a great app for SOTA activity. It works better when offline than Pocket SOTA (which often happens when you are activating a summit).

For ham radio license training, I like the HamRadioSchool.com apps. (OK, I am biased here as I contribute to that web site.)

HamRadioSchool Technician (Author: Peak Programming, Cost: $2.99) There are a lot of Technician practice exams out there but this is the best one, especially if you use the HamRadioSchool.com license book.

HamRadioSchool General (Author: Peak Programming, Cost: $2.99) This is the General class practice exam, especially good for use with the HamRadioSchool.com book.

Morse Code is always a fun area for software apps:

Morse-It (Author: Francis Bonnin, Cost: $0.99) This app decodes and sends Morse audio. There are fancier apps out there but this one does a lot for $1.

Well, that’s my list. Any other suggestions?

– Bob K0NR

The post The Completely Updated Incomplete List of Ham Radio iPhone Apps appeared first on The KØNR Radio Site.

The Android HT – Part 3

The Android HT – Part 3

The Android HT – Part 2

The Android HT – Part 2

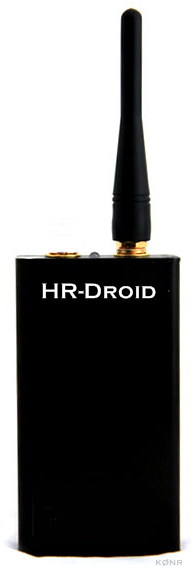

My article on the Android HT generated some interesting comments and ideas. Thanks so much! One of the main themes in the feedback is to have the radio be “faceless”, with the user interface done on a mobile device (i.e., smartphone or tablet). The mobile device would communicate to the transceiver via Bluetooth (or maybe WiFi). This approach has the advantage of separating the radio hardware (which probably doesn’t need to change very often) from the compute/display hardware (which is on a faster-paced technology path). I went ahead and hacked together a concept photo of such a device (click the photo to enlarge it). This device could interface with any mobile device that has a Bluetooth interface, so it would be independent of OS on the mobile device (yes, you could use your iPhone).

My article on the Android HT generated some interesting comments and ideas. Thanks so much! One of the main themes in the feedback is to have the radio be “faceless”, with the user interface done on a mobile device (i.e., smartphone or tablet). The mobile device would communicate to the transceiver via Bluetooth (or maybe WiFi). This approach has the advantage of separating the radio hardware (which probably doesn’t need to change very often) from the compute/display hardware (which is on a faster-paced technology path). I went ahead and hacked together a concept photo of such a device (click the photo to enlarge it). This device could interface with any mobile device that has a Bluetooth interface, so it would be independent of OS on the mobile device (yes, you could use your iPhone).

Such an approach opens up a variety of use models. Imagine sticking the transceiver in your backpack and using an app on your smartphone to enjoy QSOs when hiking. Alternatively, the radio could hang on your belt. At home, the radio could be left in some convenient location, connected to an external antenna on the roof and operated from the mobile device. (Low power Bluetooth is said to have a range of about 10 Meters.) These are just a few thoughts…I am sure you can think of others.

I would expect the original Android HT concept to be easier to use for casual operation, due to the All-In-One Design with dedicated hardware volume control, channel select and PTT switch. I am assuming those functions would be implemented in software in the faceless implementation, which would likely be less convenient. Most mobile devices have their own GPS system included, so that would mean one less thing that has to be in the radio.

The other idea that surfaced in the feedback is using Software Defined Radio (SDR) technology to implement the transceiver. This would provide a higher degree of flexibility in generating and decoding signals, enabling additional areas of innovation. That is a great idea and will require a whole ‘nuther line of thinking.

73, Bob K0NR